"Cinderella at 75: How a Princess and Glass Slippers Revived Disney"

- By Nathan

- Apr 19,2025

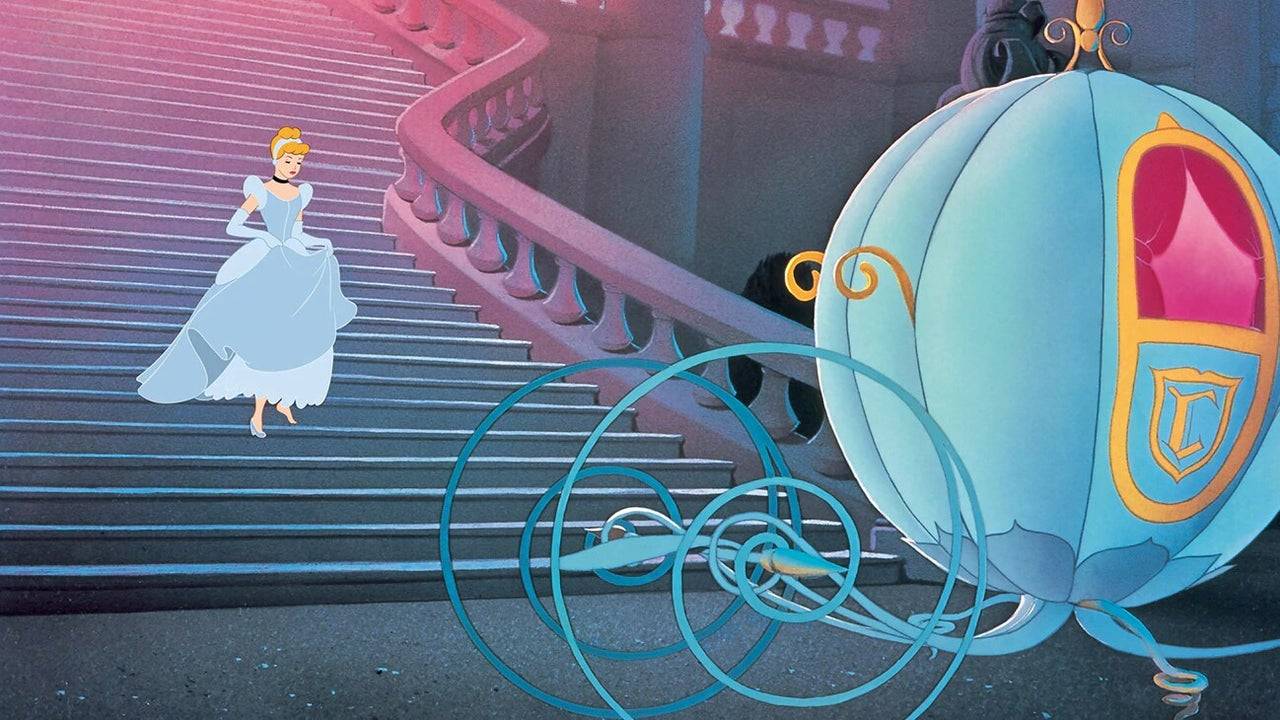

Just as Cinderella's fairy tale was poised to end at midnight, so too was The Walt Disney Company on the brink of financial collapse in 1947, burdened by a $4 million debt following the box office disappointments of Pinocchio, Fantasia, and Bambi amidst the turmoil of World War II and other challenges. However, the enchanting story of Cinderella and her iconic glass slippers played a pivotal role in rescuing Disney from an untimely end to its animation legacy.

As Cinderella celebrates its 75th anniversary of its wide release today, March 4, we had the opportunity to speak with several Disney insiders who continue to draw inspiration from this timeless tale of rags to riches. This narrative not only echoed Walt Disney's own journey but also rekindled hope for the company and a post-war world yearning for something to believe in once more.

The Right Film at the Right Time --------------------------------To fully appreciate the significance of Cinderella, we must revisit Disney's own fairy godmother moment in 1937 with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Its unprecedented success as the highest-grossing film until Gone with the Wind took the crown two years later enabled Disney to establish its studio in Burbank, still its headquarters today, and paved the way for a series of feature-length animated films.

However, Pinocchio, released in 1940 with a budget of $2.6 million, fell short despite its critical acclaim and Academy Awards for Best Original Score and Best Original Song. This trend continued with Fantasia and Bambi, as they too failed to meet financial expectations. The primary reason was the onset of World War II, triggered by Germany's invasion of Poland in September 1939, which severely impacted Disney's European markets.

“Disney's European markets dried up during the war, and the films weren’t being shown there, so releases like Pinocchio and Bambi did not do well,” Eric Goldberg, co-director of Pocahontas and lead animator on Aladdin’s Genie, explained. “And before long, Disney was overtaken by the U.S. government to produce training and propaganda films for the Army and Navy. Throughout the 1940s, the studio produced what they called Package Films like Make Mine Music, Fun and Fancy Free, and Melody Time. These projects were excellent, but they lacked a cohesive narrative from start to finish.”

Package Films were compilations of short cartoons assembled into feature-length movies. Disney produced six such films between Bambi in 1942 and Cinderella in 1950, including Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros, which were part of the U.S. Good Neighbor Policy aimed at countering Nazi influence in South America. While these films managed to break even and Fun and Fancy Free reduced the studio’s debt from $4.2 million to $3 million in 1947, they hindered the production of true feature-length animated stories.

“I wanted to get back into the feature field,” Walt Disney said in 1956, as recorded in The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney by Michael Barrier. “But it required investment and time. A good cartoon feature takes a lot of time and money. My brother [Disney CEO Roy O. Disney] and I had quite a disagreement... It was one of my big upsets... I said we’re going to either go forward, get back in business, or liquidate or sell out.”

Faced with the possibility of selling his shares and leaving the company, Walt and Roy chose the more challenging path and bet everything on their first major animated feature since Bambi. If this gamble failed, it could have spelled the end for Disney’s animation studio.

"I think the world needed the idea that we can come out from the ashes and have something beautiful happen." “At this time, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, and Cinderella were all in various stages of development, but Cinderella was chosen as the first to be produced due to its similarities to the successful Snow White. Moreover, Walt believed the story could offer something beyond mere entertainment.

“Walt was adept at reflecting the times, and I think he recognized what America needed after the war was hope and joy,” said Tori Cranner, Art Collections Manager at Walt Disney Animation Research Library. “While Pinocchio is an incredibly beautiful film, it's not a joyful movie in the way Cinderella is. The world needed the idea that we can rise from the ashes and witness something beautiful. Cinderella was the perfect choice for that moment in time.”

Cinderella and Disney’s Rags to Riches Tale

Walt’s fascination with Cinderella dates back to 1922 when he created a short film during his time at Laugh-O-Gram Studios, the precursor to Disney. The story, adapted from Charles Perrault’s 1697 version, resonated with Walt as it embodied the classic theme of good versus evil, true love, and the realization of dreams—a rags-to-riches narrative that mirrored his own aspirations.

“Snow White was a kind and simple girl who believed in wishing and waiting for her Prince Charming,” Walt Disney remarked, as captured in footage from Disney’s Cinderella: The Making of a Masterpiece DVD special feature. “Cinderella, on the other hand, was more practical. She believed in dreams, but she also took action to make them happen. When Prince Charming didn’t come to her, she went to the palace and found him herself.”

Cinderella’s resilience in the face of adversity, despite being mistreated by her Evil Stepmother and Stepsisters, mirrored Walt’s own journey from humble beginnings through numerous failures to relentless pursuit of his dream.

This story remained with Walt, leading to another attempt in 1933 to revive it as a Silly Symphony short. However, the project grew in scope and complexity, ultimately leading to a decision in 1938 to transform it into a feature film. Despite delays due to the war and other factors, the film evolved over a decade into the beloved classic we know today.

Disney’s success with Cinderella can be attributed to the studio's ability to enhance these timeless tales with global appeal. “Disney excelled at taking these age-old fairytales and infusing them with his unique touch, bringing his taste, entertainment sense, heart, and passion into the narrative, making audiences connect with the characters and story more deeply than in the original tales,” Goldberg said. “These fairytales were often grim, serving as cautionary tales. Disney, however, made them universally enjoyable and timeless.”

"She believed in dreams all right, but she also believed in doing something about them." Disney achieved this with Cinderella by introducing her animal friends—Jaq, Gus, and the delightful birds—as comic relief and confidants, allowing Cinderella to express her true self. The Fairy Godmother, reimagined as a more relatable, bumbling grandmother figure by animator Milt Kahl, added warmth and charm. The iconic transformation scene, where Cinderella's belief in her dream manifests into a life-changing night, remains one of the most memorable moments in cinema history.

The animation of Cinderella’s dress transformation, often cited as Walt’s favorite, was masterfully crafted by Disney Legends Marc Davis and George Rowley. “Every single sparkle was hand-drawn on every frame and then hand-painted, which is simply mind-blowing,” Cranner said. “There’s also a subtle moment during the transformation where the magic pauses for a fraction of a second before her dress changes, adding to the scene's enchantment.”

Thanks so much for all your questions about Cinderella! Before we sign off, enjoy this pencil test footage of original animation drawings of the transformation scene, animated by Marc Davis and George Rowley. Thanks for joining us! #AskDisneyAnimation pic.twitter.com/2LquCBHX6F

— Disney Animation (@DisneyAnimation) February 15, 2020

Another unique Disney addition is the breaking of one glass slipper, a detail not found in earlier versions, which underscores Cinderella’s agency and strength. “Cinderella is not a bland protagonist; she has a distinct personality and strength,” Goldberg noted. “When the stepmother breaks the glass slipper, Cinderella reveals the other one she had kept, showcasing her control and cleverness.”

Cinderella's determination to stand up for herself throughout the story is both inspiring and empowering, contributing to the film's global success. The movie premiered in Boston on February 15, 1950, and its wide release on March 4 that year was a triumph, grossing $7 million on a $2.2 million budget, making it the sixth-highest-grossing film of 1950 and earning three Academy Award nominations.

“When Cinderella was released, critics hailed it as a return to form for Walt Disney,” Goldberg remarked. “It was a massive success because it brought back the narrative features like Snow White that audiences adored. The studio regained its momentum, leading to the development of films like Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty, 101 Dalmatians, The Jungle Book, and many more—all thanks to Cinderella.”

75 Years Later, Cinderella’s Magic Lives On

Seventy-five years later, Cinderella’s influence continues to grow within Disney and beyond. Her castle stands as an iconic symbol at Walt Disney World and Tokyo Disneyland, and her story inspires the opening sequences of many Disney films.

Her legacy is evident in modern Disney classics, such as the dress transformation scene in Frozen. “When we animated Elsa’s dress transformation in Frozen, co-director Jennifer Lee wanted it to pay homage to Cinderella,” said Becky Bresee, lead animator on Frozen 2 and Wish. “The sparkles and effects around Elsa’s dress directly connect to Cinderella’s transformation, honoring the impact of the earlier films.”

The contributions of the legendary Nine Old Men and Mary Blair further enriched Cinderella, giving it its distinctive style and character. As we reflect on this timeless tale, Eric Goldberg’s words encapsulate the enduring message of Cinderella: “The big thing about Cinderella is hope. It gives people hope that perseverance and strength can lead to a positive outcome. Its biggest message is that hope can be realized, and dreams can come true, no matter the era.”

Latest News

more >-

-

- 2025 D&D Starter Guide

- Dec 26,2025

-

-

-

- GTA 6 Delayed Until May 2026

- Dec 25,2025